Colour trademarks and its protection

Traditionally, trademarks have been associated with those represented by letters, numbers or words (word marks), by images or drawings (figurative marks) or by a combination of the two (mixed marks); however, the market, together with new ways and techniques of presenting marks in marking, have led to the development over time of new types of marks, known as non-conventional marks. One such type of marking is the colour marking.

Nowadays and for some time now, marketing has gained enormous weight in the market and in companies, as the image with which a business, a product or a service is associated becomes its calling card. How many times have we not associated a particular colour with a company just by seeing it? For example, the colour purple? Milka chocolate. A red drink? Coca-Cola. A blue social network? Facebook, now Meta.

In other words, consumers are able to relate a product and service to a company’s origin. However, if in general one of the requirements for the registration of a trademark is that it must have distinctive character, this is even more accentuated in the case of coloured trademarks, being much more demanding in this type of trademarks.

Both the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) and the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (SPTO) describe colour marks in their regulations (EU Trademark Regulation art. 49 (2) and its Implementing Regulation in art. 3(3)(f), as well as the Trademark Law 17/2001 and its Implementing Regulation). Both regulations apply the following points to be complied with for colour marks:

- If it is a combination of colours, the systematic arrangement of the colours in a predetermined and uniform pattern must be specified.

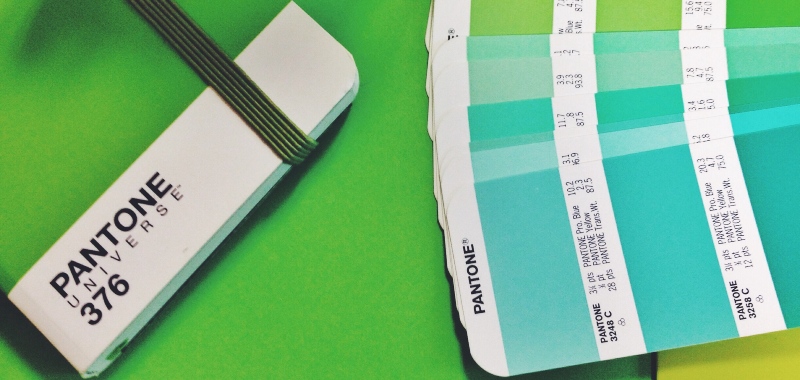

- A detailed description of the colour or colour combination must be provided. This includes identification of the colour by an internationally recognised colour code, such as the Pantone code.

- The colour mark must be distinctive. This means that it must be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, such distinctiveness being either inherent in the mark or achieved through use in trade.

The EUIPO guidelines provide detailed guidance on how colour marks are examined. These guidelines can be found at the following link: EUIPO guidelines on colour marks

However, it must be borne in mind that the registration of a colour as a trademark is somewhat exceptional. And this is so because, as in all industrial and intellectual property rights, a kind of ‘monopoly’ is being granted with respect to the good that is the object of protection, and in this case, with respect to a specific colour, empowering its owner to prevent third parties from using this registered colour in trade for the same goods and services. For this reason, it will be necessary to demonstrate that the colour in question has acquired distinctiveness for the goods and services it designates, which is known as ‘secondary meaning’ or supervening distinctiveness, which implies that the consumer has a direct relationship between the colour in question and a specific product or service.

One of the most famous cases was that of Christian Louboutin and his shoes, and in particular, the red colour applied to the sole of the shoes. Louboutin shoes have been the subject of several lawsuits related to the use of the red sole colour, but the one that received the most media coverage was against the prestigious Yves Saint Laurent brand in Europe. Although the distinctiveness of its iconic sole was initially not recognised, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that it did have rights to it.

More recently, there was the case concerning the Red Bull trademark (T-101/15) where a company of Polish origin disputed the validity of the registration of Red Bull on the grounds of lack of distinctive character.

The Court indicated that, as has been affirmed since the Sieckmann judgment, the graphic representation ‘must be clear, precise, self-contained, intelligible, durable and objective’. In other words, and from the point of view that the court came to interpret the above, ‘a sign must always be perceived in an unequivocal, uniform and durable manner’. In Red Bull’s mark, therefore, such a graphic representation would allow for different combinations of the two colours and that the accompanying descriptions ‘do not provide additional precision with respect to the systematic arrangement associating the colours in a predetermined and uniform manner’. This is why both the Invalidity Division, and later the Board of Appeal, confirmed that such a colour mark consisted only of juxtaposition of two colours in the abstract and without contours.

As can be seen, in the world of trademarks, being in possession of a colour mark can give its owner enormous power over other companies in the market, which is why the offices are so restrictive in granting this type of registration.

At Letslaw we are specialists in industrial property, as well as in advising on everything related to trademarks and trade names, which is why we do not hesitate to provide you with any kind of advice you may need.

IP/IT lawyer.